At this rate, we’ll need ten more federal elections to reach gender parity in Ottawa

January 12, 2022

2021 marked the centennial anniversary of the first woman to be elected to the House of Commons in Canada, Agnes Macphail. But, despite dramatic shifts toward greater gender parity in politics over the last 100 years, women are still vastly underrepresented in office. This bore out again this September when Canadians elected 235 men and just 103 women to serve as their MPs, an increase of 3 women from the previous Parliament. 70% of elected federal officials in 2021 are men. With more public calls for gender parity, why is this social change so slow to come?

Compelling answers to this question already exist and point to several reasons. A 2019 CBC article investigated the relationship between gender, party financial support and election outcomes. The conclusion? Female politicians are more likely to be set up to fail – they are more likely to run in hard to win ridings, and less likely to receive financial support from their parties compared to male candidates. Other explanations point to gender bias in candidate preference or argue that parties and institutions have failed to make safe spaces in Canadian politics for women. As a result of these additional barriers, among others, women have a steeper hill to climb than men when convincing the public that they are electable.

Are women less electable than men?

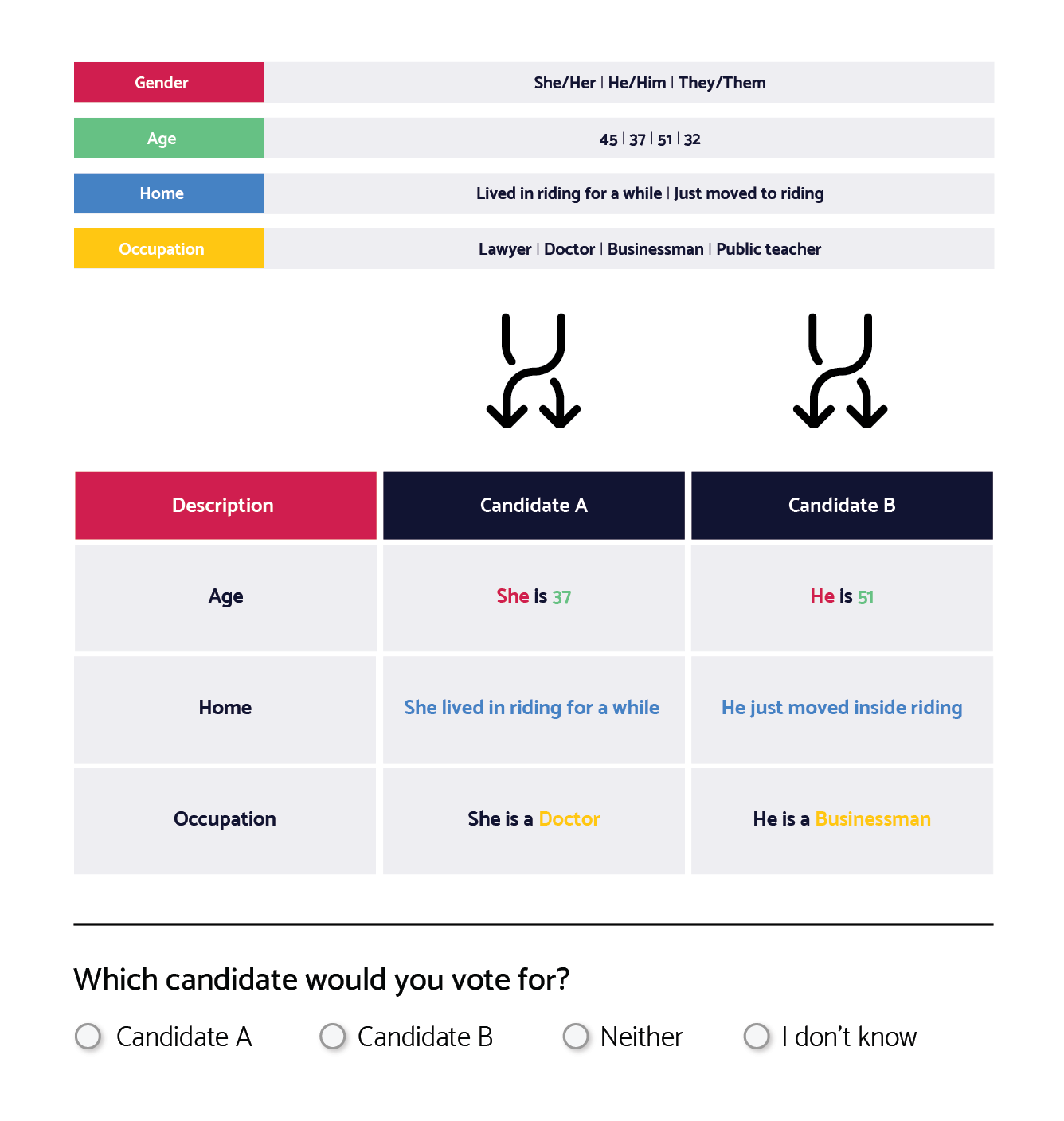

In 2020, Data Sciences conducted an internal online experiment using a technique referred to as a conjoint analysis in the social sciences. When using traditional polling methods, survey respondents sometimes answer questions as though someone was looking over their shoulder. They may indicate support for the candidates who they think they’re supposed to support, even if in real life they would actually vote for someone else.

Conjoint analyses aim to reduce these biases by measuring effects as it does not ask respondents to relay opinions, and only measure the impact of particular traits indirectly and subtly. In our experiment, respondents were exposed to pairs of randomly generated candidate profiles and asked to make a few choices between each pair. Importantly, a number of personal and professional traits were varied among the hypothetical candidates, including their upbringing, their family, their career, their experience, and their age. Gender was randomly assigned and subtly indicated by the use of either male or female pronouns (e.g. “She has lived in the riding for five years” or “He was a doctor before getting into politics”.) A representative sample of over 5,000 Canadians participated in this experiment and rated thousands of combinations of traits. We then used statistical methods to assess the impacts of each trait on the perceptions of the candidates.

Our results suggest that all else being equal, being female actually provides a slight boost to a politician’s popularity and credibility: women were generally more likely to collect respondents’ votes (+2.8%) and were more likely to be perceived as sharing the respondent’s values (+3.7%) and be seen as an effective MP (+1.7%)

So, the Canadian public is open to electing women. However, being female (vs. male) was also associated with a 2% decrease in perceived likelihood to win.

This may seem like a small effect, but it is important to note that in September, 45 MPs were elected by a margin of 5% or less. For close races, these biases, especially when combined with our electoral system, can make a big difference. Approximately 22% of Canadians considered themselves primarily strategic voters1 at the time of our survey – that is, they would not vote for their preferred candidate, but rather for the candidate that was most conducive to the government they wanted to see in Ottawa. Instead of voting for the Liberals or the NDP, they voted against a Conservative leadership or vice versa. Nearly ¼ of the country voted for the ‘tolerable’ candidate in their riding that they believed most likely to win. Nearly ¼ of the country voted for the ‘tolerable’ candidate in their riding that they believed most likely to win. The impact of gender on perceived electability and election outcomes in this system is difficult to estimate, but to put that into more concrete terms, 10 ridings in Canada won by men in 2021 could have been the result of this bias in perception (where the difference in vote share was within 4% between male and female candidates and the female candidate came in second).

Another finding was that throughout the experiment, women were more frequently penalized for failing to be “ideal” candidates. Negative traits had a larger negative impact on female (vs. male) candidates. Having a privileged background was a disadvantage for any candidate, but more so for women, driving down their support by an additional 7.6% compared to men. We observe the same effect for female newcomers; female candidates who were described as ‘new to politics’ were less likely to receive support (-5.6%) compared to male candidates. This is doubly penalizing, as the historical legacy of gender imbalanced Parliaments means that women are not only more likely to be newcomers but will also be more heavily penalized for lack of experience by the electorate, creating a vicious cycle that will require dedicated effort to break. In comparison, none of the tested traits that could impact a candidate’s perceived electability — e.g. age, experience — had a more negative impact on men than on women.

One possible reason why voters may believe that women are less likely to be elected is that voters do, consistently, see female candidates lose more often than male candidates. This election was no exception. Among the five federal parties with Parliamentary representation, 18% of female candidates won their election, compared to 31% of their male counterparts.

Can gender parity efforts contend with the power of incumbency?

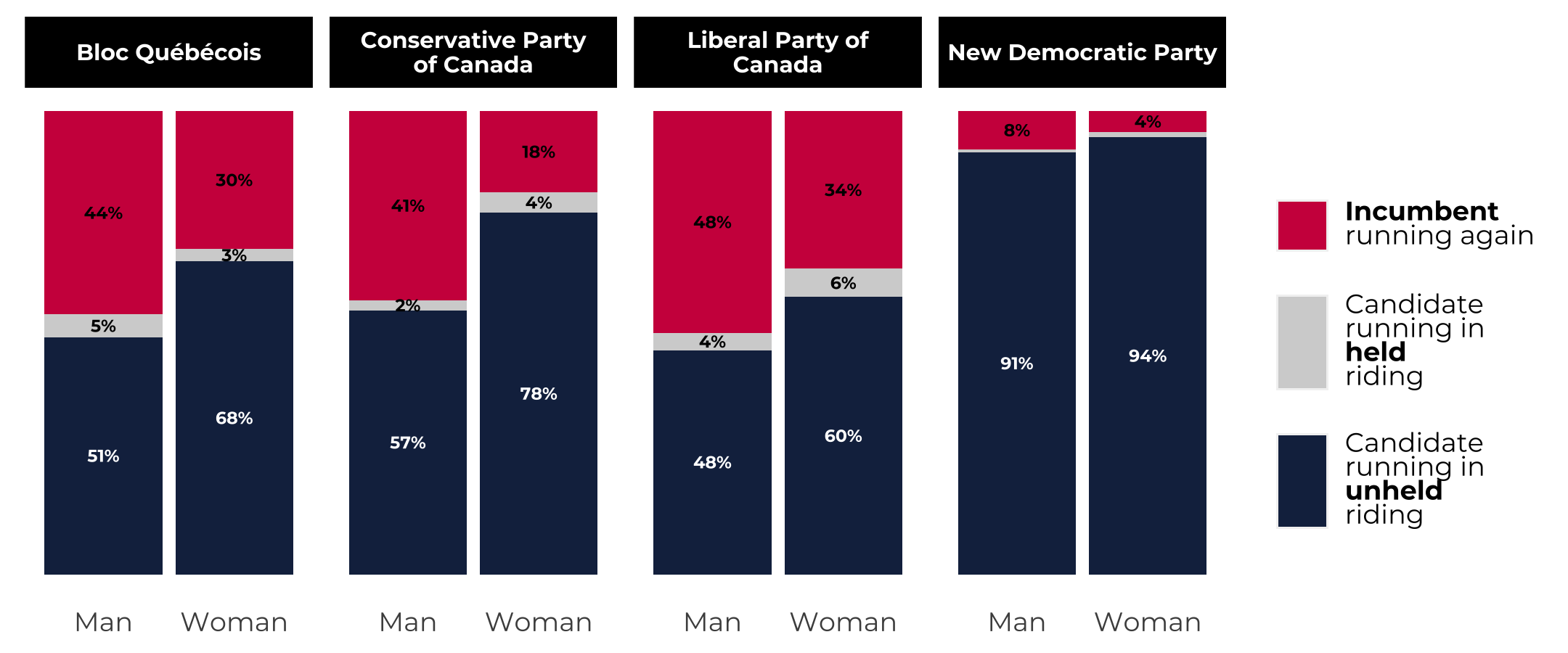

This effect is partially structural. Politicians are historically much more likely to be male, so incumbents – who win at a higher rate than not – tend to be men. In fact, 69% of 2021 candidates running in seats that had been won by their parties since in or since 2015 were men. 2021 female candidates running for the four major political parties were more likely than their male counterparts to run in harder-to-win, unheld ridings (see graph).

One of the best opportunities parties have to support women in politics is to encourage and promote the nomination of female candidates when a spot in a ‘safe riding’ opens up, i.e. when a male incumbent decides not to run again in an upcoming election. In 2021, this does appear to be happening:

- The Conservative Party of Canada replaced 2 female and 7 male incumbents with 4 female and 5 male candidates, doubling the number of female candidates running in these held seats;

- The Liberal Party of Canada replaced 4 female and 10 male incumbents with 8 female and 6 male candidates2, also doubling female representation in this cohort;

- The New Democratic Party replaced 1 female and 2 male incumbent with 2 female and 1 male candidate, a 33% increase;

- As the only party that already achieved gender parity at 47% female representation, the Bloc was the only party that did not use incumbent’s exits to boost female representation in 2021, replacing one male and one female incumbent with two male candidates.

In case the advantage of this position wasn’t clear, these newcomer candidates running in previously held ridings did appear to wield the advantage: 90% were elected as MPs.

Formally reserving these opportunities for female candidates is one strategy that could be used to increase gender parity. However, it cannot be over-relied upon. Only a minority of incumbents retire each election cycle, and not every male incumbent will be replaced by a female candidate.

At our current rate of turnover and replacement, it might take another 10 federal elections before we reach gender parity standards in Ottawa unless other actions are taken.

What more can we do?

Reaching gender parity in government isn’t going to happen solely by encouraging women to run, although these efforts must be continued. Parties and other political institutions need to recognize that there are real barriers women and other members of underrepresented groups face when running for office and be strategic – while also ensuring that once elected, women and minority group members are supported and that a reasonable course of action can be taken to address any discrimination3. Upholding gender parity in cohorts of nominated candidates and in the cabinet, promoting more examples of women and gender diverse individuals in public leadership roles, increasing representation of these individuals in their strongholds, and helping to increase funding support for candidates from under-represented groups are just some other actions political organizations can take to increase diversity among their ranks. Recent successes of women in key municipal elections in Quebec are auspicious signs for our future, and hopefully unpacking these wins will elucidate strategies for other women running for office in the future.

Lastly, to work towards greater diversity of thought and perspective in government, we will need data. To our knowledge, there are no publically available datasets that can speak to the realities of other minority group candidates in Canadian politics. As such, we were unable to include these groups in our analysis, but doing so could have provided important nuance to our findings. Vital segments of our society – including BIPOC, members of the 2SLGBTQ+ community, or people from lower economic status backgrounds – are crucially underrepresented in the House. How underrepresented is hard to measure at this moment. Elections Canada and others should consider implementing programs to release key indicators of diversity goals and inclusion in government to enable tracking of these important metrics over time. Canadians are ready for more diversity of representation in federal politics— but whether this is achieved in the short term or in 100 years depends on our capacity to understand and analyze our political system’s shortcomings, and implement effective strategies to overcome them.

Footnotes

- 74% reported voting for the leader or the party values, while 4% cited other reasons.

- This includes all Liberal candidates who were running, at the time of writ drop, in a riding that had an incumbent Liberal MP (excluding formerly Liberal independent MPs).

- For example, the Standing Committee on the Status of Women through their investigation found that 67% of female MPs experience gender based heckling in the House of Commons, compared to only 20% of their male colleagues.