Addressing Canada’s housing affordability crisis

September 18, 2023

This blog provides information on findings as part of our Greyhound research project.

Canada is in the midst of a housing affordability crisis. Renters and owners alike have seen their housing costs rise consistently, leading many to question how we got here, and what we can do to make housing more affordable. Experts and commentators point to a number of interrelated factors as culprits, including chronic insufficiencies in housing supply, financialization and speculation in the housing market, exclusionary zoning policies and cumbersome approval processes , and a general lack of affordable housing units, to name a few. In any case, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) estimates that housing was last affordable in 2003 and 2004. Today, home ownership is no longer a viable option for many middle class Canadians due to record-high home prices coupled with high mortgage interest rates. Meanwhile, soaring rent prices in or near urban centers like Vancouver and Toronto severely limit the housing options of middle and lower income earners.

With these challenges in mind, we conducted an online, nationally representative survey among 1,000 Canadians in March 2023 to gauge how Canadians feel about the housing affordability crisis, and which policies they think are most effective at addressing it.

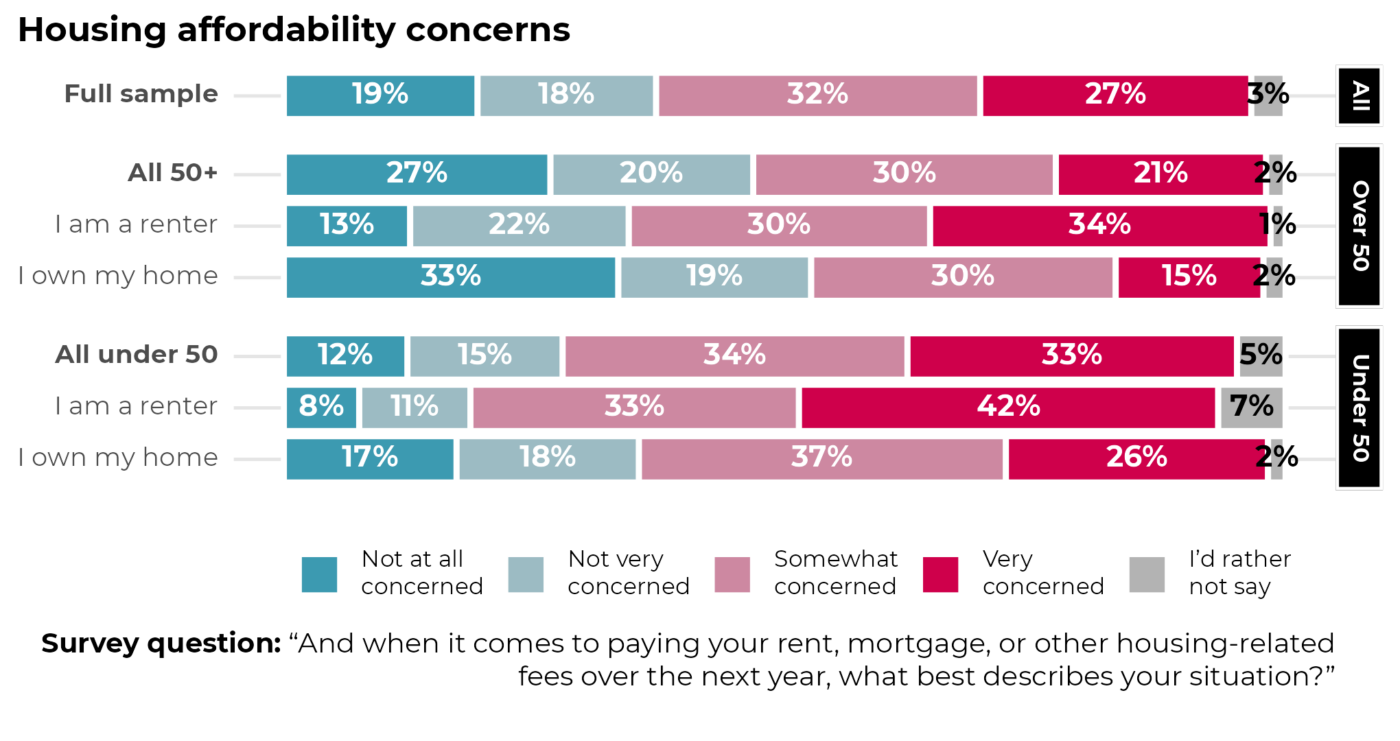

Most Canadians are at least somewhat concerned about meeting their housing costs, especially younger renters

When we asked Canadians about their housing costs, 59% said they were somewhat or very concerned about meeting their housing-related costs over the next year. This concern is strongly tied to both age and tenure (i.e. whether one’s dwelling is owned or rented). For instance, older (50+) homeowners — who are far more likely to have paid off their mortgages — were significantly less concerned (45%) than average, while younger (under 50) homeowners were somewhat more concerned (63%) than average. When it comes to rented accommodation, older renters were somewhat more concerned than average about meeting their housing costs (64%), while three-quarters younger renters were concerned. Overall, these results suggest that, although rising housing costs have put pressure on both renters and owners, this pressure is leading to greater concern among younger renters.

Given these concerns, it has become increasingly important to enact policies that will meaningfully address housing affordability in Canada. However, not everyone agrees on which policies are most effective — these opinions are coloured by one’s perceptions of the underlying causes of the housing crisis, one’s position in the housing market, and — inevitably — one’s broader political beliefs. Our goal here is not to adjudicate between which policies are best, but rather to understand which policies are most palatable, and to whom.

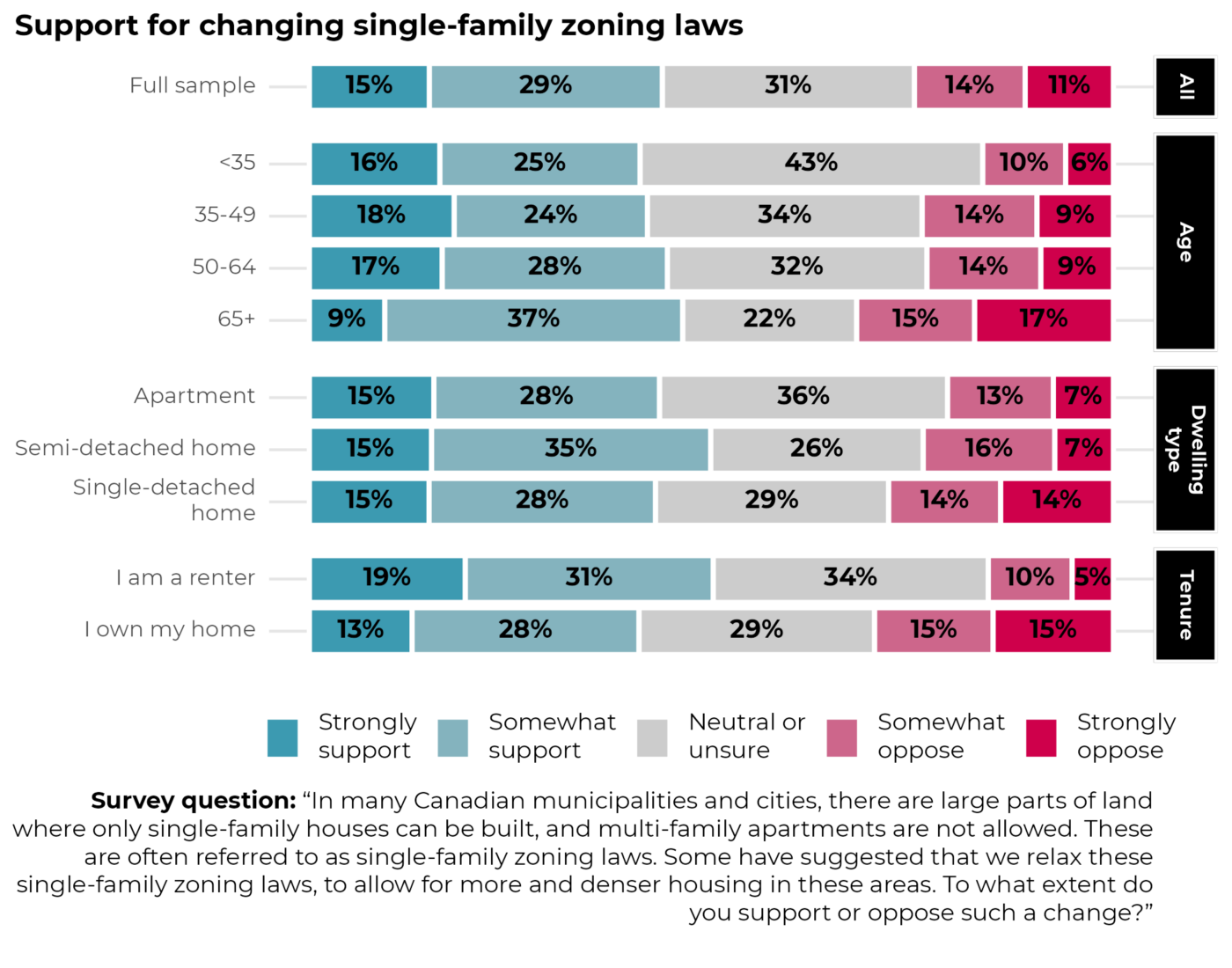

Few Canadians are opposed to allowing more density in areas zoned for single-family homes

One policy that comes up often in debates over housing affordability is so-called single family zoning laws. Typically, these laws limit the type of housing that can be built on a plot of land to include only single-family homes, excluding other types of housing like duplexes, townhouses, and apartments.

To many, this type of zoning preserves some of the family-oriented traits we desire in our homes and neighborhoods, including character, quality of life, yards and garden space, and privacy. However, when it comes to housing affordability, opponents argue that single family zoning laws drive up housing costs by creating scarcity in housing supply, particularly in areas with high demand. Some also point to issues such as suburban sprawl, car-dependency, segregation, and negative environmental consequences.

Considering that single-family homes make up over half of all dwellings in Canada, we asked Canadians whether they support changes to single-family zoning laws that would allow for more density. The average person has probably not given much thought to residential land use regulation and, because of this, we find that a significant proportion (31%) of respondents are neutral or unsure when it comes to whether zoning laws should change (this is especially true of younger respondents and renters). However, the bulk of respondents (44%) would support a policy of relaxing single-family zoning laws to allow for more density, while only 25% oppose such a change.

Interestingly, those who live in single-detached homes were equally as likely to support changing zoning laws, compared to apartment dwellers. At the same time, single-detached home dwellers were less neutral than apartment dwellers, which means they also disagreed somewhat more.

Though zoning laws are typically in the domain of municipal governments, provincial governments have become increasingly involved. Along these lines, the city of Victoria recently passed the Missing Middle Housing Initiative, which will replace single-family zoning and allow for the construction of multiple units on single lots. At the same time, the province of British Columbia plans to introduce its own legislation that will allow for 3 to 4 units on traditional single-family lots.

When we asked Canadians who should have the most authority when it comes to the laws surrounding single-family zoning, the bulk of respondents (37%) believe that municipal governments should have the most say, while 23% believe these decisions should be in the hands of the residents of the neighborhoods where the laws are being changed. Though relatively few said that higher levels of government should have this authority, younger respondents (under 35) were more likely to say that the federal (21%) or provincial (23%) governments should be in charge.

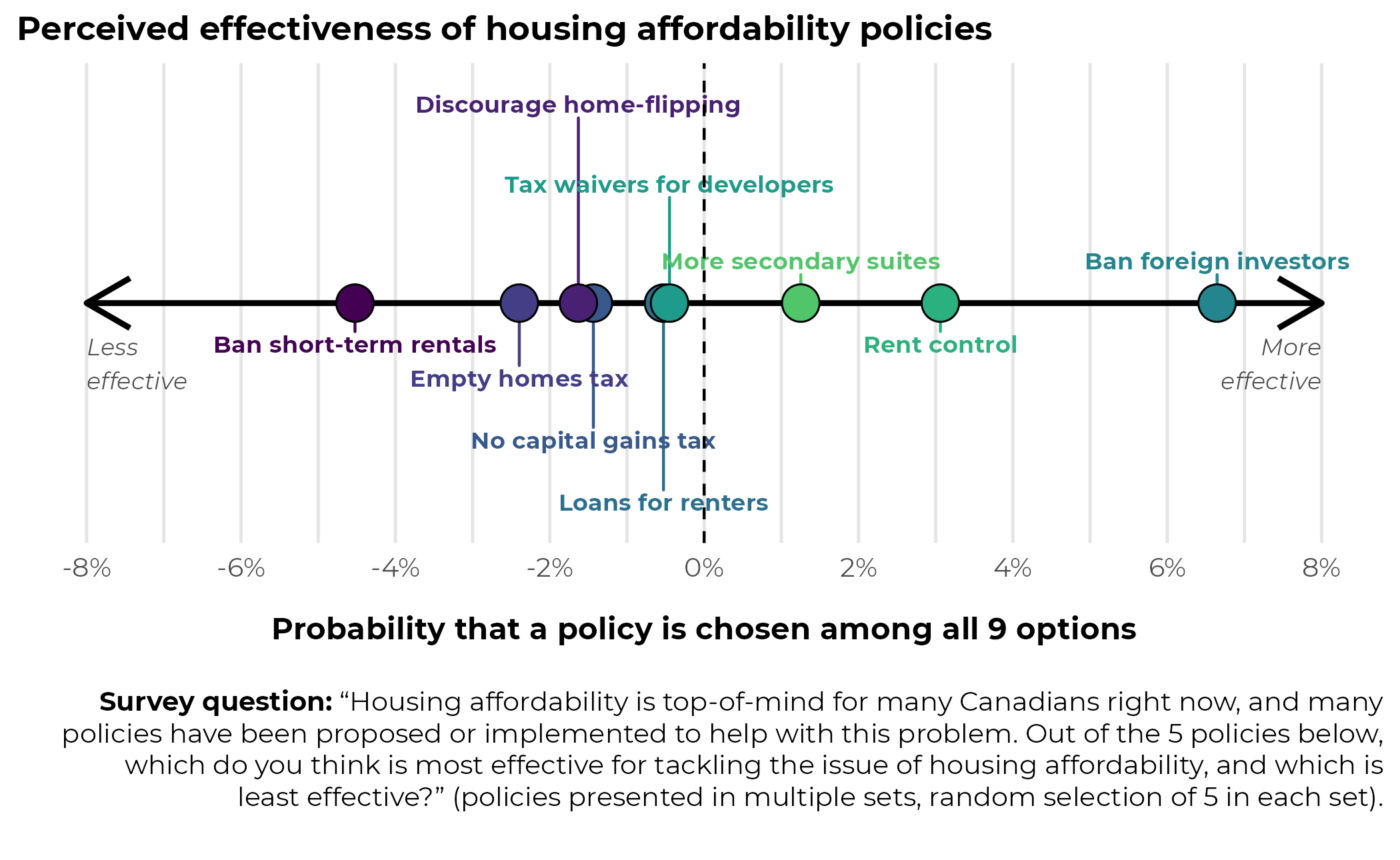

Banning foreign real estate investment is seen as an effective policy, banning short-term rentals less so

Amending our single-family zoning laws to allow for more density is one of many policies either directly or indirectly aimed at addressing the housing affordability crisis. There is, of course, no “silver bullet” policy that can completely solve the problem, and not everyone agrees on which policies are most effective. For this reason, we asked respondents to choose from a randomized and iterated list of housing policies — some of which are already in effect to some extent, and others that have only been proposed — which they think are most and least effective at addressing the housing affordability crisis.1 Our results suggest that some policies are seen as more effective than others.

Overall, respondents deemed banning foreign investors who do not live in Canada from buying homes as most effective, a policy which actually came into effect at the start of this year. They were around 7% more likely to select this policy over the other 8 policies. It should be noted, however, that some experts question whether foreign investment is a driving factor in rising home prices; for instance, in Ontario, only 3.4% of residential properties have non-resident owners.

The second-most popular policy among our respondents was rent (or vacancy) control — that is, connecting rent to the housing unit rather than the tenant, so that landlords cannot increase the rent when a tenant leaves. This policy — not enacted in most Canadian provinces and territories, with some exceptions — is hotly debated. Though there is significant nuance between different forms of vacancy control, supporters generally argue that it helps renters by disincentivizing evictions and profiteering by landlords, while detractors argue that it makes it harder for landlords to cover their rising costs and may hurt renters in the long run by disincentivizing the construction of new rental housing. A somewhat less controversial policy — allowing more secondary suites in homes — followed in third place. A number of other policies fell somewhere in the middle, including waiving some taxes and fees for developers who build affordable homes, providing interest-free loans to renters who are at risk of eviction, charging no capital gains tax on the sale of one’s primary residence, and discouraging home flipping. Charging an annual tax of 5% of a home’s value to owners who leave their secondary homes empty — a policy in place in Vancouver — was seen as somewhat less effective.

Notably, Quebecers were more likely to consider banning short-term rentals as an effective policy. Recently, a deadly fire in an Old Montreal apartment building, where many illegal Airbnbs are reported to have been operating, has led to increased scrutiny toward short-term rentals. Because we surveyed respondents before this fire occurred, it seems likely that Quebecers, especially those in Montreal, have become even more amenable to increased restrictions on short-term rentals.

1 This survey method is often referred to as a Maximum Difference Scaling, “MaxDiff”, or Best Worst Scaling analysis design. We computed probabilities that respondents would choose an action over another one using a random parameter logit model (“Hierarchical Bayes”).

Though there is no “silver bullet”, understanding public sentiment toward housing policy can help guide solutions

To some extent, the results from our survey into housing affordability confirmed what is already widely known: many Canadians are deeply concerned about meeting their housing costs. What is less clear, however, is which policies Canadians see as most effective for bringing us out of the housing affordability crisis. Overall, we find little opposition to the idea of allowing more density in areas traditionally zoned for single-family homes, which, if enacted, may help increase housing supply. Moreover, banning foreign real estate investment was seen as one of the most effective policies for addressing the crisis, while banning short-term rentals was seen as less effective. Ultimately, housing policies fall under the jurisdiction of and will require coordination across municipal, provincial, and federal levels of government. Understanding which policies are most palatable among the Canadian public, along with comprehensive research into best practices from other jurisdictions, will inform policymakers as they devise potential solutions.

Appendix

| Short Description | Full text shown to respondents |

|---|---|

| Rent control | Connecting rent to the housing unit rather than the tenant, so that landlords cannot increase the rent when a tenant leaves. |

| Loans for renters | Providing interest-free loans to renters who are at risk of eviction because of financial challenges. |

| Ban short-term rentals | Banning short-term rentals (e.g. VRBO, Airbnb). |

| Empty homes tax | Charging an annual tax of 5% of a home’s value to owners who leave their secondary homes empty. |

| More secondary suites | Allowing more secondary suites in homes (e.g. basement or garden suites, laneway houses). |

| No capital gains tax | Charging no tax (capital gains) on the sale of one’s primary residence. |

| Discourage home-flipping | Discourage ‘home-flipping’ by requiring Canadians to hold their property for at least 12 months. |

| Ban foreign investors | Banning foreign investors who do not live in Canada from buying homes. |

| Tax waivers for developers | Waiving some taxes and fees for developers who build affordable homes. |